|

|

|

Book of AbstractsBook of Abstracts

Keynote Speaker ‘Art, advertising and national pride in the 1951 Festival of Britain programme’ Susan Finding, Université de Poitiers The 1951 Festival of Britain was intended as a showpiece to display the country’s achievements to the world, extolling its way of life. The official Festival guide, as well as containing explanations about the various exhibition sites and exhibits, comprises sixty-four full-page colour adverts for British companies and British-made products. No industry or manufacturer was permitted to book exhibition space within the South Bank Exhibition. Exhibits were ‘selected for the excellence of their design and their appropriateness to the story which is told’. This is likely to have also been the case for the adverts placed in the guide, a further way of putting Britain on display. The overall narrative related by the Festival is found echoed in these pages. In these pieces of artwork, both visual and textual references abound to British ‘heritage’, to a glorious future, to the literary canon, with artistic tropes projecting both tradition and futuristic visions and, as seen at the time, the place of Britain in the world.

Panel 1 Placing Art: Finding the Unexpected within the Ordinary “Boy on the Bike”: recycling culture in a Hovis advertisement? The 1973 Hovis “Boy on the Bike” television advertisement, directed by Ridley Scott, is one of Britain’s most well-known, regularly ranking amongst favourites in surveys, rescreened on several occasions and parodied by The Two Ronnies in 1978. A 2019 Kantar survey found it to be the most “iconic” and “heart-warming” British advert of the past 60 years, leading the British Film Institute and Ridley Scott Associates to collaborate on a remastered version screened in 2019. The advert shows a boy struggling to push his bike up a steep cobblestone hill to deliver a heavy basket of loaves to “Old Ma Peggoty’s place”, before freewheeling back down to the bakery where, we are told, a hot drink and thick slices of warm, freshly baked bread await him: “'T'was a grand ride back though. I knew baker’d have kettle on and doorsteps of hot Hovis ready.” The voiceover is that of the delivery boy, now an old man, nostalgically reminiscing over his younger years. The theme can be traced back to Scott’s first film “Boy and Bicycle” (1965), which follows his younger brother Tony, cycling round West Hartlepool and Seaton Carew, to a musical backdrop including a brass band. Describing the advert in 2019, Ridley Scott declared: “I remember the filming process like it was yesterday, and its success represents the power of the advert. It taught me that when you combine the appropriate music and the appropriate film, you have liftoff.” The music is borrowed from the main theme of the second movement of Dvorak’s Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, performed for the advert by Ashington Colliery Brass Band, also from the North East of England, like the Scott brothers who began their art studies in West Harlepool. This paper will explore the enduring memory, (and commercial reminders), of the advert, its nostalgic representations of a bygone era, its suggestion of a lost heritage of northern, working-class England. Is this merely commodification and re-appropriation of classical music for commercial purposes such as selling cars or bread. Does this involve “flattening out” of culture, as Theodor Adorno argues, depriving the original of context, artistic depth, and critical possibilities, or does it build other cultural forms? What are the implications, if, as John Storey observes, it is perhaps no longer possible “… to hear the second movement from Dvorak’s New World Symphony, without conjuring up an image of Hovis bread?”

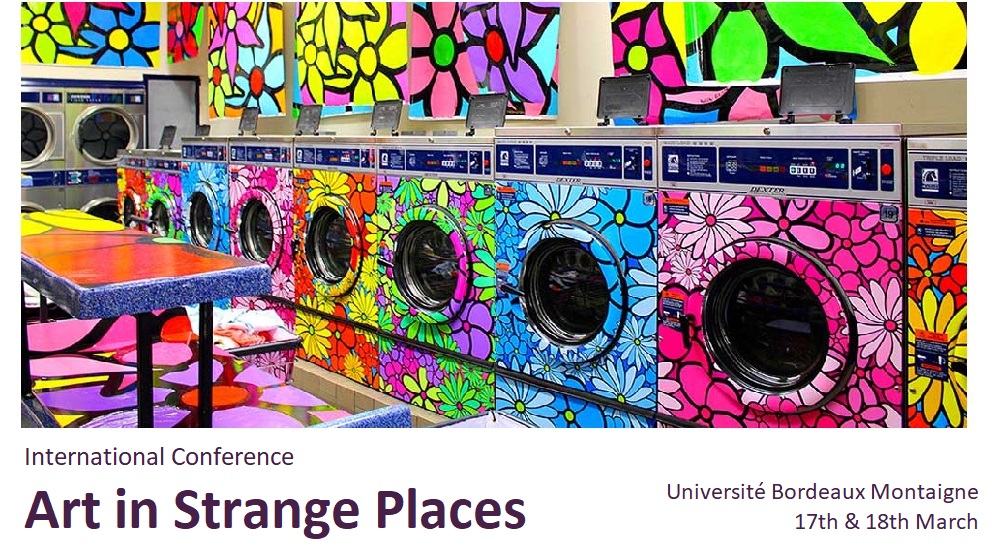

Strange Exhibition Venues: Laundrettes, Buses and Canteens as Gallery Spaces in 1970s Britain My proposal will examine exhibition practices developed in the 1970s which deliberately chose to show artwork in unusual places. In a context characterised by the absence of photographic galleries, young photographers in the 1970s made the pragmatic choice of showing their work in places associated with the ordinary and the mundane. As far away as it is possible to imagine from the legitimate spaces of art, laundrettes, pubs and buses were turned into temporary galleries. To an emerging generation of British documentary photographers in the early 1970s, at a time when photography remained associated with the commercial sphere and was barely considered as an artform, the desire to show their work in outlets other than the illustrated press meant that they had to create their own exhibition spaces, at the lowest cost possible. Before the creation of one of the first photographic galleries, the Half Moon Gallery in London’s East End, photographers like Paul Trevor used laundrettes to display his work. Around the same time, Daniel Meadows converted a double-decker bus into a living unit and an darkroom with a small exhibition space, before travelling across England and Wales. Nick Hedges created his own exhibition in the cantines of the West Midlands factories where he had spent time with and photographed the workers. In Handsworth, Brian Homer, Derek Bishton and John Reardon set up a street studio on the pavement to help make and display self-portraits of the people in the community. After the creation of the Half Moon Gallery in 1972, its touring exhibitions travelled on their own in trains, ready to be collected at the point of delivery. Beyond providing places for photographers to make their work known, these various examples point to a desire to make art a familiar and accessible experience in the more mundane of places. These initiatives thus participated in the challenge to elitist conceptions of art : they made the point that art that should not be reserved to the more conventionally legitimate artistic institutions and cater to gallery-going publics, but should rather be found in the most commonplace sites, and be democratic in access.

“Extraordinary Art, Unexpected Places.” The Successes and Failures of British Public Art The spectacular rise in the commissioning of public art the United Kingdom has experienced in the last few decades – a rise inaugurated principally under the impulse of New Labour who calibrated much of its support to the cultural industries according to their potential regenerative impact on depressed areas around the country – has been accompanied by the development of structures experimenting with the unusual, often surprising, placement of art in the environment. In the wake of the institutional critique movement, sites beyond the gallery have offered fresh perspectives. Yet, far from simply getting rid of both a roof and an academy, the use of mostly urban public space has triggered new reflections on the varying degrees of publicness of both art and the city that accommodates it. Britain has been at the forefront of a privatisation of public space, and this has changed the way art occupies outside locations there. Artists who have made location an integral part of their practice have often favoured ruined environments, recession-hit shops, or in-between spaces which are often readily accessible because it saves owners costs on security, maintenance and business rates taxed on empty buildings. Besides their economical advantages, these interim spaces, disused offices, or houses (but also whole areas under redevelopment like King’s Cross) also provide interesting unstable backgrounds against which the works are created – all the while running the risk of being co-opted by commercial interests and a new pop-up culture. I would like to present how different commissioning agencies operating in Britain (FutureCity, or Modus Operandi who commission on the part of clients, Artangel who function as patrons for artists’ more ambitious projects and whose slogan is “Extraordinary art, Unexpected Places,” or ArtReach who do both) have grappled differently with the vested interests behind simply applying a percent for art policy, placemaking, or instrumentalising ephemeral installations and performances for footfall, either within the Art in empty spaces programme or in some of the country’s numerous POPs (business incentive districts) and the process of gentrification they often foster.

Panel 2 Public Bodies, Private Emotions: the Restorative Powers of Expression Mouths, Texts and ‘Radical Elocution’ I will explore the c19th phenomenon of famous literary texts rehoused/repurposed as pieces for performance in elocution manuals and textbooks. I will look at how some key pieces of art took on new life in the mouths of c19th schoolchildren in the US and Britain, who would perform these pieces as forms of recitation and oratory. My argument will be to show how this phenomenon allowed for what I call ‘radical elocution’, with art in strange places serving surprising political agendas.

Poetry in hospital – hospital in poetry I propose to examine the role of poetry in hospitals in the UK. Poetry seems to have been playing an increasing role in the NHS, and Guy’s and St-Thomas’ hospitals for instance actually celebrated the 70 years of the institution by posting on their website a two-minute-long rhyming poem, with a quite regular beat, each line said by an NHS staff member. Still for the 70th anniversary, the Welsh poet Owen Sheers was commissioned to write a long poem (more than a 100 page long) entitled To Provide all people (borrowing Bevan in 1945). The poetic quality of both poems (website and Sheers) is quite “low,” the purpose being to reach the highest number of people. One may wonder then why the poetic genre was favoured. To what extent is it thought to affect “all people” more immediately than prose texts or videos? This celebratory purpose is not the only use of poetry in hospital. In recent years, poetry writing workshops have multiplied in hospitals – one initiated by Fiona Sampson, for instance, a renowned poetry scholar – to help patients narrate (and thus make sense of) their own experience. It is considered, by some people, as part of the therapeutic protocol when the patients “make [their] land in order.” The poetic production in hospital has also been promoted and awarded since 2009 by the Hippocrates Prize for Poetry and Medicine (likewise headed by Michael Hulse, a poetry scholar): it has drawn a large number of medical students and medical staff whose poetic production has literally boomed. It seems then (and this needs to be proven) that the experience of hospital (as a professional or a patient) is a growing source of inspiration – the ontological and existential crisis the patient goes through, the various difficulties met by the medical staff, the intimacy with death, and the sonorous peculiarity of the words of medicine, all seem to offer a fruitful combination for poetic inspiration. I also want to examine how poems (written by poets) set in hospital actually sometimes refer to the role of arts in this institution. Dana Arnolds insists that hospitals have long been “the nexus of social and cultural activities”1. This is evoked by Julia Darling in “How to Negotiate Hospital Corridors” in which she stops on “the art that someone has battled / to hang onto the walls”, diverting, for the length of a stanza, the roaming patient from his condition and turning him into a transient “art critic.” Sarah Broom (NZ poet who lived in the UK) remarks that “there is poetry all over the walls / of oncology”; and Hannah Sullivan’s repeated image of the “wizened nectarines on the windowsill” appears as a haunting still (and yet real) life; as for Deryn Rees-Jones, sitting in the hospital waiting-room, she goes through the “posters” on the walls, the “small frame oil of horses racing” and a “canvas” with birds and geese surrounding a woman. The tone of the poem will be examined and the apparent incongruity of the place or of the art may be assessed. I propose to conclude with a presentation of Simon Armitage’s “The Flags of the Nations.” It is a found poem (a ready-made): Armitage literally reproduced on the page a poster he took from the hospital wall – one that explains the strict disciplinary regulation of waste disposal. The poet then literally makes art with some hospital material. We are no longer dealing with arts in strange places, but rather with the odd displacement of performative encoded language with hygienic purpose, into the artistic space of poetry (a Faber&Faber collection of poems). 1 Dana Arnold. The Spaces of the Hospital – Spatiality and Urban Change in London 1680-1820. Routledge, 2013.

Funerary art in CWGC cemeteries: from contestation to acceptance, During and after WWI, hundreds of thousands of human bodies were hastily buried in the devastated grounds of continental Europe, particularly on the battlefields of Flanders, Artois and the Somme. Many soldiers were still missing, and hundreds of corpses had yet to be recovered, while some could not even be reached. The British Government then made a decision that was striking to the public: they would not repatriate the corpses of soldiers from the British Empire, but instead bury them close to the place where they fell, in perpetual resting places designed on grounds given by the French and Belgian peoples. Many mourning families wanted their father, their brother, or their son to be buried at home, and declared this decision to be a form of “National Socialism,” calling it a bereavement controlled by the State. In order to implement the British government and the newly founded Imperial War Graves Commission’s resolution, their members began a process of bringing together artists with diverse skills and different visions (such as Sir Herbert Baker, Sir Reginald Blomfield, Sir Edwin Lutyens, Charles Holden, Rudyard Kipling, Leslie MacDonald Gill…) to work together, and asked them to make suggestions that might be acceptable to most families. Sir Frederic Kenyon, then Director of the British Museum, was appointed “with a view to focussing, and, if possible, reconciling the various opinions on this subject that had found expression among the Armies at the front and the general public at home, and particularly in artistic circles.” What were the differences of opinion, what aesthetic choices were made, and for what reasons? What artistic movement(s), if any, influenced the artists involved in this gigantic architectural program, ‘the single biggest bit of work since any of the pharaohs’, in the 1920s? The study of the necropolis boundaries, the patterns and inscriptions on headstones, the monuments (‘crosses of sacrifice’, ‘stones of remembrance’, shelters…) and the horticultural design say much about the goals that were targeted. They simply explain how this group of formidable architects tried to succeed, through the essence of their art, in rendering mourning and distance an easier burden to bear for bereaved families.

Panel 3 Body Art andthe Art of the Body The Body as Museum on the Move : Remediation, Ubiquitous Art and Fictionalising the Self Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage by Turner literally reduced to the size of a thumb-nail, Banksy’s Girl with a Balloon fully inked on a back, or Francis Bacon’s disturbingly screaming Pope worn as an effigy printed on a tee-shirt, these are only but a few of the many examples one can think of and find when looking for signs of the contemporary reproduction craze of artworks circulating in seemingly strange places. Once we take home, say, Millais’ Ophelia, after a stint at the museum, we can still admire it as framed on a fridge magnet. We are then left with the possibility of assigning to the object the power of a memory trigger, much in the way Proust describes his famous remembrance of the past after savouring the madeleine. My paper aims to address the possible connections between remediated artworks (Bolter & Grusin 1999) and what might be called a ‘fluctuating mnemonic property’ particularly of interest when famous artworks are shown and seen on the body (nails, skin, clothes). I will examine changes in scale, format, texture, surface, mobility, all of which makes those images more ubiquitous, both in the public and private sphere, yet inevitably devoid of their usual Benjaminian aura. While the commercial motivation of promoting and selling art-inspired garments and accessories such as a scarf, or a handbag cannot be denied, as it articulates once again a high-low gap, my talk will rather discuss the paradoxical process of relocating and reproducing artworks by focusing, first on the materiality of the original piece and how the latter morphs (or not) into a means of fictionalising the self. I will further show how such shifts in cultural and aesthetic categories (Ngai 2012) can contribute to widening the scope of what Henry Jenkins has defined as ‘convergence culture’ (Jenkins 2006). In that respect I will argue that museum-like bodies are part of a larger trend that generates and disseminates all manners of afterlives, a process whereby the use of words like ‘heritage’, ‘aura’ and perhaps ‘art’ itself is potentially challenged and pushed to its limits.

Venuses on the Instagram. Survival of the “Figura Serpentinata” in the Age of the Social Media Despite being reproduced on the t-shirts, coasters, cups, travel mugs, blankets, or handbags, Leonardo’s Leda, Botticelli’s three Graces, or Giambologna’s bathing Venus could hardly talk about followers until they have begun to sail the seven seas of Instagram. Top ten website’s stars like Kylie Jenner, Kim Kardashian, Selena Gomez, Ariana Grande, or Beyoncé, followed by the hundreds of thousands of girls and women around the globe, they all avidly draw on the renaissance invention of “figura serpentinata” and curve their bodies accordingly in the countless pool, sea, or bathroom selfies. As if the dream of Balzac’s famous “Unknown Masterpiece” came true and while “looking for a picture, [we stood] before a woman.” The question is: what happened to the heritage of the serpentine figure that the Instagram selfies keep on exploiting? The paper will pick up the threads of the already published research (“Figura Serpentinata Unleashed: Hogarth’s Line of Beauty and the Misreading of Lomazzo’s Treatise,” in Umění/Art, LXV/5–6, 2018) and explicate the genealogy of the “Instagram Venuses,” leading from Hogarth’s repolarization of the renaissance concept through the 19th and 20th-century embrace of the “liberated” line to the specific contemporary inversion of the mind-body dualism that has mingled with the artistic tradition. The trick is that the original “figura serpentinata”, readily compatible and symbiotic with the renaissance Neoplatonic thought, presented the spiritual trajectory of the erotic animation, culminating in the desired transcendence. Most importantly, such trajectory was read as the specific seizure that dematerializes bodies and makes them transparent. However, after the disposal of the Neoplatonic background and the loosely yet demonstrably related 19th-century hygienic translations, the up-to-date epigone of the “figura serpentinata” turned into a folded line, becoming a surface seismograph of the internal bodily passions promised to expose themselves behind the scenes or the closed doors of the “paid areas,” as in the case of the new phenomenon of “OnlyFans.” To sum it up in just one sentence, while the original “figura serpentinata” served as the philosophically enriched safeguard preventing the erotic contour from becoming openly sexual and orgiastic, the contemporary selfie-line blossoms as the visual vocabulary of lust.

The Human Canvas: Artistic Tattoos in Edwardian Britain Béatrice Laurent, Universirté Bordeaux Montaigne In 1910, Hector Hugh Munro (aka Saki) published ‘The Background’, an intriguing short-story relating the tragedy of Henri Deplis, a Luxembourger whose life becomes a nightmare after he acquires a beautiful artistic tattoo during a stay in Italy. Robbed of his identity as a person, Deplis becomes a human canvas whose only worth is inscribed in ink in the skin of his back. Saki is well-known for his mischievous satires of Edwardian culture, and the fictional Italian tattooist Signor Pincini may well have been inspired by British practioners of the needle such as Sutherland Macdonald (1860-1942), Tom Riley, and Alfred South who became celebrities in late Victorian and Edwardian London. Catering to the tastes of an affluent clientèle, these artists sometimes created, and more often replicated, paintings on the bodies of their customers. Taking Saki’s short-story as a starting point, we will look at the intertwined issues of art ownership, of copyright legislation and of the status of tattoing at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Panel 4 Getting a Hold on Art: the Object(s) of Discussion Nouvelles frontières des objets : formes, usages et statuts Mobiles par essence comme tous les objets, certains le sont encore plus que d’autres car leur longue migration les pousse vers des formes nouvelles, leur procure des statuts différents ou implique des usages parfois inattendus. Ainsi en va-t-il des «objets frontière», ces objets produits en Europe avec des artificialia ou des naturalia extra-européens. Issues de divers types de modification matérielle de l’objet venu des antipodes, de telles productions conservent présents la distance et le trajet accompli. Peut-être même les valorisent-elles, dans leur nouvelle existence, à la frontière de l’ici et de l’ailleurs ? Cette catégorie d’objets récemment définis comme « frontière » rassemble de nombreux cas de matières, de natures et de provenances diverses, de la Renaissance à nos jours : objets de porcelaine de Chine montés ou commodes de laque orientale du XVIIIe siècle au XXe siècle, oeuvres de Rodin composées à partir de sculptures pré-colombiennes, nautiles devenus hanaps du XVIe siècle au XIXe siècle, œuf d’autruche- ostensoir d’Othoniel. À chaque fois, même si l’objet « initial » continue d’exister, la réinvention est totale et atteint le plus souvent à la fois son statut et son usage. Pour éclairer la manière dont se forment les « nouvelles frontières » formelles, utilitaires et statutaires des objets venus d’ailleurs, on se concentrera autour de quelques cas d’étude, en particulier, sur l’œuvre réalisée par le duo d’artistes Baltensperger + Siepert, en collaboration avec des exilés, dans le cadre du projet Ways to Escape One’s Former Country / Patterns & Traces (2017). La transformation définitive opérée sur le tapis d’Orient ancien sous la forme d’un tissu noir noué suivant les méandres de la route de l’exil des êtres et des objets modifie complètement la perception de l’artefact oriental. D’objet de luxe enrichissant un intérieur européen, le tapis devient une œuvre d’art suscitant la réflexion sur les courants migratoires. Par la modification des formes, des usages et des statuts, de tels objets atteignent de nouvelles frontières et engagent à une redéfinition de l’identité humaine, comme multiple et ambivalente, composée aussi des lieux traversés ainsi que de la temporalité associée à la spatialité puisqu’en un espace-temps unique est donné accès à une infinité de mondes. La similarité des trajets des objets et des hommes donne, en effet, dans pareil cas, une pertinence particulière à la notion de biographie des objets. À la fois produit de la migration et moyen de la percevoir, le rôle de l’art peut être à son tour également précisé.

Detours through canonisation: the use of Omega Workshop prints as Bloomsbury Group “Merch” After a revival of interest in the 1980s, the Omega Workshops (a design collective that ran from 1913 to 1919) are mostly known today via their association to members of the Bloomsbury group and the presence of pieces at Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex. After being fully immersed in the colourful and unique world of Charleston during the proposed one hour tour, visitors might enter the on-site gift shop. Inside, they might be tempted to purchase their own piece of homeware or stationary bearing an Omega Workshop (or Omega inspired) design. While still recognising the joy to be found in bringing home a piece of Bloomsbury Bohemia, this paper aims to question whether these items might not undermine as much as they celebrate the legacy of the Omega Workshops. Rather than placing already canonised works on everyday objects, certain items of Bloomsbury « merch » actually participate in a canonising of the chosen pieces – and perhaps in such a way that goes against the collective’s initial aims. Roger Fry, founder and director of the Omega Workshops sought to dissolve the divide between the decorative arts and the fine arts. He was insistent that all their productions should be anonymous – signed only with the Greek symbol omega – to ensure they be judged only on artistic merit. Certain prints were used to create a line of “Bloomsbury” products by CustomWorks. This manufacturer used Omega prints on notebooks and coasters in the same way they do works by Van Gogh, Monet or Picasso. This close association with canonical works reasserts the barrier between decorative and fine arts, presenting the works as canonised pieces. Further pushing the distinction is the supplementary information found on the back of the notebook, serving as a sort of museum label and framing the work in canonical terms. This also traces the prints back to their original artists hence going directly against the initial principles and interest in the items may come from more of a fascination with the artists as famous historical figures rather than from the works’ own aesthetic merits. While the printing of Omega Workshop designs onto different products might superficially be congruent with the Omega Workshops’ initial aims, there is also a distortion of their legacy due to the means through which these ends are achieved. The desired goal is subjected to a detour through canonisation. This paper will compare different lines of products, and analyse their keeping with the legacy of the works they promote, in order to invite reflection on the differences between relating to a work as canonicaland relating to it on aesthetic merits.

Illustrating beyond the page and book: English literary classics in most unexpected places Literary classics have not only been retold but also refashioned in multiple ways. Imitations, parodies, abridgements, sequels and prequels are among the most famous forms of retelling of literary texts, while stage and screen adaptations are among their most famous forms of refashioning. As far as the graphic and visual arts go, book illustrations, and perhaps, to a lesser extent, paintings, have been considered as the most obvious and widespread forms of visual interpretation of famous literary texts. It is perhaps less known that a whole variety of prints in varied shapes and formats have been made based on literary illustrations and paintings and sold both in street and online shops to decorate homes or offices around the world, sometimes very far from the original texts’ contexts of creation and production. Such printed or painted and sometimes framed images have not only taken literature beyond book pages and covers into the realm of visual culture and the various places that have accommodated said culture through the years; they have also been used and recycled to create literary by-products of all types, ranging from advertising cards and posters to homely objects (tableware, cupboard knobs, decorative tiles, fridge magnets and even shower curtains, to name only a few), as well as toys and games, clothes and accessories and yet other items and objects. Collectively, these by-products have taken literary texts and some of their iconic images into varied socio-cultural, geographical and temporal spheres and converted them to sundry non-literary uses. They have granted them a visual and material dimension that has either renewed or simply assured their presence in a multiplicity of places and guaranteed their prolonged popular success, often without the originating texts themselves and outside the books that have circulated these texts. Some of these afterlives have imparted iconic literary characters and scenes with an ornamental or a practical function and transformed them into artefacts, relating them to the decorative or applied arts rather than the “fine” arts. Altogether, these sundry afterlives testify to the potential of literary classics to keep attracting visual and material refashioners, as well as to the evolution of the mediums and media available for refashioning literary texts in more or less artistic forms and styles. This paper proposes to look at Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as an example of the transformation of a canonical literary text into an endless range of items relating to both visual culture and material culture, and to assess the effects of that transformation on the perception and prestige of Carroll’s text and, more globally, of literature at large. It will put to the fore the modes of interaction between literary texts and literary objects and question the “high art” status of canonical literature and the “low art” status of its innumerable and multifarious manifestations in popular culture. The range of literary afterlives inspired by Alice being extremely vast, I will focus on those literary images and objects that occupy the most unexpected places and spaces – in the home as well as on the human body. |

| Online user: 2 | Privacy |

|